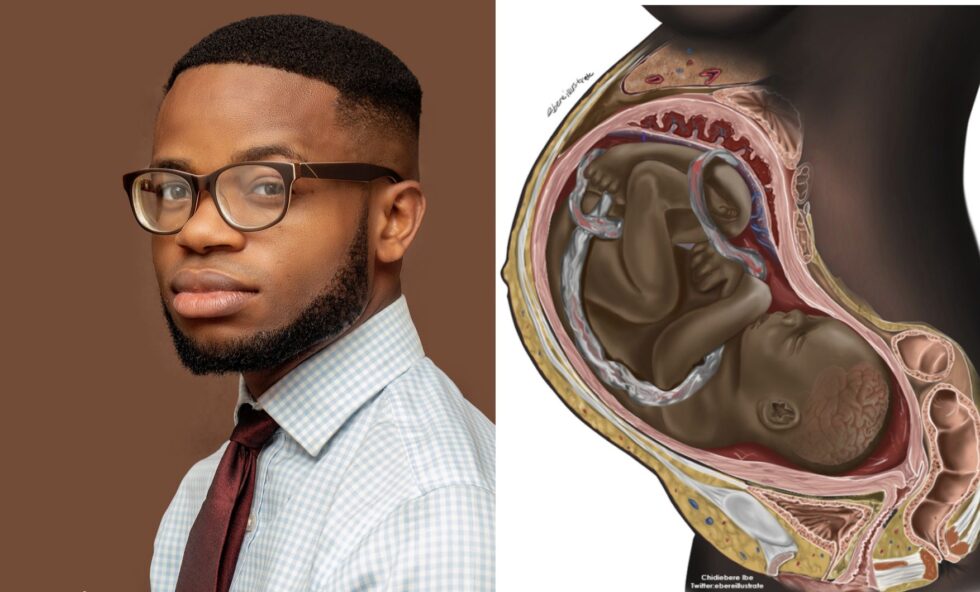

Recently, I saw an illustration of a fetus in its mother’s womb that gave me pause. There was nothing inherently unique about this illustration, except this was the first time I had ever seen a medical illustration of a Black mother and fetus.

I was not the only one struck by this image. The illustration went viral and sparked a (long overdue) conversation about diversity in medical textbooks.

The creator behind this illustration is Chidiebere Ibe, a medical student who currently works as a chief illustrator at the International Center of Genetic Diseases at Harvard Medical School and the creative director of the Journal of Global Neurosurgery.

I sat with Ibe to discuss his work and its implications for medical practitioners worldwide. When asked about his current projects, Ibe said he is “focused on creating more artwork … for publications and textbooks, and for the company that I work for to promote equity in healthcare through my diverse images.”

He believed that the image went viral because of healthcare disparities between Black and White women, “where Black women are not receiving equal healthcare attention as the White person receives. There was [sic] a lot of statistics that showed… there was a high mortality rate among Black women compared to White women…. That image came as a tool of advocacy… when it was needed the most.”

Ibe said that the image “came as a shock to the world,” stirring up much-needed conversations between medical practitioners and patients about the lack of representation they had seen in healthcare.

Even after 50 years in the industry, one medical professional noted, “I have never seen an image of such, ever, in a medical textbook.”

Students trained to serve in medical professions were only used to seeing White images in their medical textbooks and, as Ibe maintains, “they never thought about anything other than the White [patient].”

Publicly sharing this illustration of the Black mother and fetus sparked conversations about how to improve and update the medical curriculum, how to include more of these images, and how these images can help improve healthcare outcomes. Ibe believes these diverse images can and will help meet the ultimate goal of improving healthcare outcomes for those who have been consistently underrepresented.

Ibe said that the creation of these diverse images, and openness within the medical community to use them as a powerful tool to improve healthcare outcomes, has inspired other artists to change their images from White to Black. He believes having these diverse images in hospitals and healthcare facilities will improve the outcomes – specifically for Black pregnant women who are often given unequal healthcare attention.

As of April 2022, according to the CDC, “Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than White women. Multiple factors contribute to these disparities, such as variation in quality healthcare, underlying chronic conditions, structural racism, and implicit bias.”

Ibe believes that normalizing diverse images will produce a mindset change, showing that Black people deserve equal attention. “Visuals are powerful,” he said. “So when visuals are being used to address biases, I firmly believe that… the healthcare approach towards Black women … would have a greater change.”

As researchers, we hear repeatedly from underrepresented communities about how their lives have been negatively impacted by a system not designed to include them. This is not just anecdotal evidence, for the proof is in the pudding – or rather, the data.

Take skin cancer: for example, many people falsely believe that people of color (POCs) cannot get skin cancer. Yet, while people with darker skin have a lower risk of developing the disease, their survival rates once diagnosed are significantly lower as well.

Why? Because POCs are often diagnosed at a later stage.

And why are they diagnosed at a later stage? Because physicians are not taught how to identify skin cancer on darker skin or that they should even test a POC for skin cancer in the first place.

This is just one example of many. With most health conditions and diseases, POCs tend to fare worse than their White counterparts.

Currently, only 4.5% of medical illustrations depict darker skin. Ibe discussed how, in medical school, the vast majority of images presented in medical textbooks are White.

This leaves healthcare providers at a disadvantage when caring for non-White populations, as they may not know how certain conditions present themselves in POC.

In essence, diverse representation in the medical curriculum can make the difference between life and death.

When it comes to caring for diverse populations, representation is not only needed in the medical curriculum but also in clinical trials and other pharma research. In our “Mind the Gap” research series, Zebra partnered with other researchers to discuss racial disparities in medical research.

These findings included a lower trust in medical providers from Black and Hispanic populations than from the White populations surveyed. We also learned that people have drastically different lived experiences regarding healthcare and that national surveys are not representative of the opinions of POC.

It is crucial that these populations, and their views, be included in research if we are to learn how to train medical professionals to care for these populations effectively.

In addition to normalizing diverse images and including more populations in research, Ibe shared that medical outcomes will be improved by racial concordance, wherein providers come from similar backgrounds as their patients. He cited research stating that when healthcare providers look like their patients, patients feel more confident that they will be understood.

Zebra takes this idea of racial concordance from medical providers and does the same for research. Research is just as much a part of medical practice as implementation.

Racial concordance is one of Zebra Strategies’ five tenets. Zebra is dedicated to engaging researchers who look and sound like the populations they serve, allowing for deeper conversations, mutual trust and respect, and insights into experiences that lead to more effective healthcare for these communities.

As one of the few market research companies specializing in underrepresented groups, we are keenly aware of how a lack of diversity can impact someone’s life.

Ibe’s illustrations and the discussions they sparked did not surprise us. Instead, they reinforced the need to continue challenging the status quo. As Ibe has shown us, a simple illustration can have a massive impact.

Therein lies our challenge: Where else can we layer in representation to build trust and engagement within research and clinical trials?